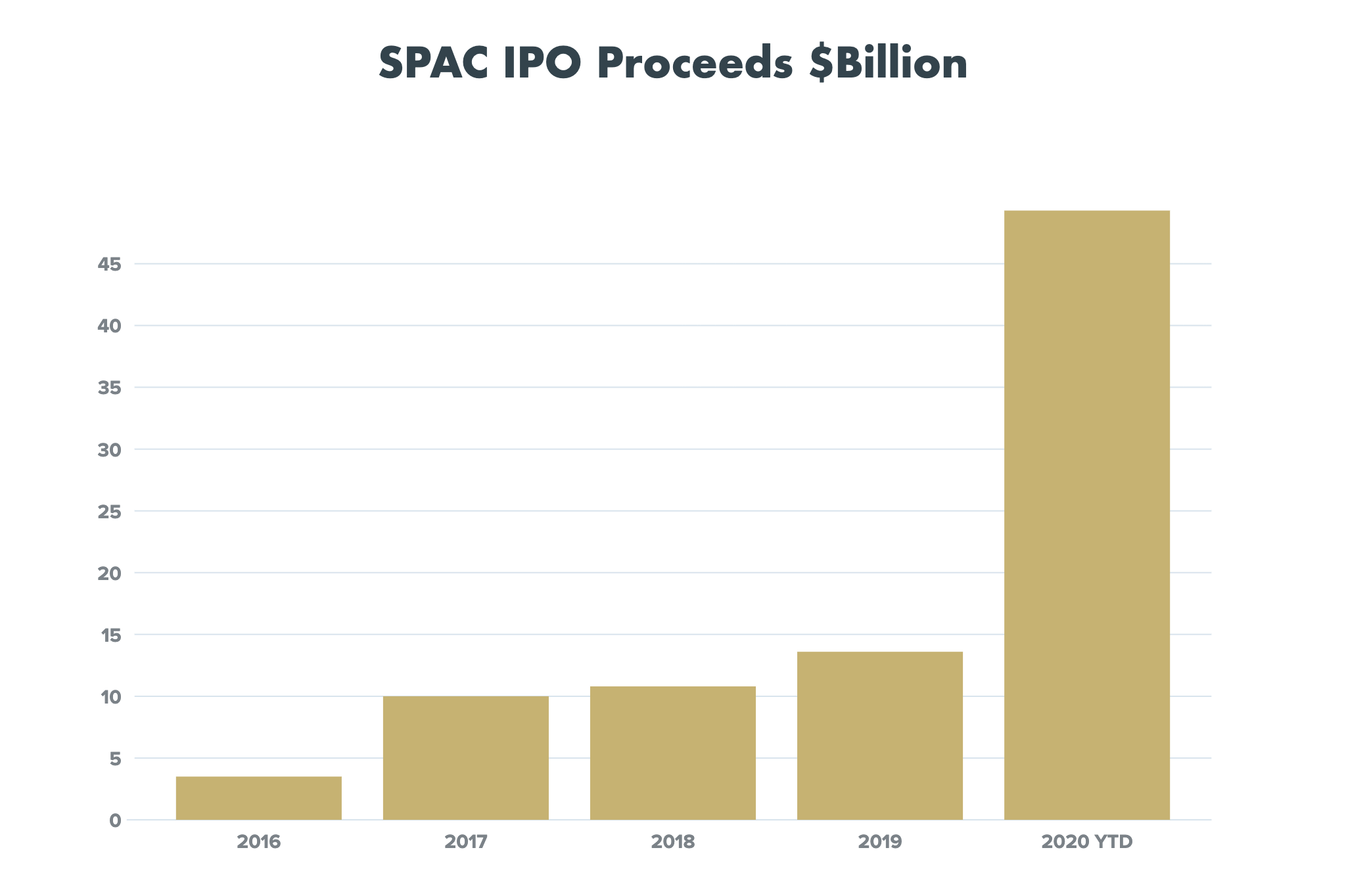

While special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have existed since the early 1990s, these investment vehicles have gained popularity in recent years. SPAC IPOs have raised over $49 billion thus far in 2020, outstripping all prior records, and many more have filed to go public by the end of the year. While in the past, most SPACs were taken public by boutique investment bankers and raised tens of millions of dollars, today, nearly every "bulge bracket" firm has led a SPACs deal, with proceeds up to hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

The enormous amount of investable capital sitting on the balance sheets of these entities — which typically have between 18 to 24 months to find a deal and deploy it — means private companies may consider the SPAC a viable path to access growth capital and achieve public status. Indeed, the market dynamics of having SPACs compete with more traditional private equity and late-stage venture funding creates a favorable environment for quality companies to negotiate favorable transaction terms. Some have argued that the SPAC provides greater certainty of outcome and a lower capital cost than the traditional IPO.

However, the SPAC structure's complexity makes it essential that management understands the advantages and potential pitfalls of these vehicles to optimize transaction outcomes.

Introduction to SPACs

Founders form SPACs for the express purpose of acquiring or merging with a private company. They seek to raise capital through an initial public offering marketed to institutional and retail investors. At least 90% of this IPO's proceeds are required to be held in the trust until the SPAC closes a business combination. SPACs don’t provide many specifics about the future operating company they may acquire and hence are referred to as “blank check” deals. But investors are often offered the opportunity to vote on any proposed acquisition. They can obtain a pro-rata distribution of the cash held in trust if they don’t like the proposed target or terms.

- SPAC sponsors are the management of the blank check company charged with completing an acquisition on favorable terms. They receive 20% ownership in the SPAC for nominal consideration, referred to as founders’ shares or the “promote.” But these shares have no claim on the cash held in trust, meaning that if the sponsors fail to close a deal, their equity stake will become worthless. In recent years, investors expect sponsors to have "skin in the game" by purchasing additional founder warrants or shares in a private placement. This funding covers the SPAC’s IPO expenses and operating costs while seeking a target so that 100% of the IPO proceeds remain in the trust. SPAC sponsors often have a background in M&A, private equity, or as successful entrepreneurs. Investors rely on their industry knowledge and negotiating expertise to source an attractive deal.

- SPAC target refers to an operating company that is either acquired by or merges with a SPAC, thereby becoming a public company. In some cases, the existing owners sell their equity. But more frequently, the infusion of capital is used to accelerate growth. Certain SPACs focus on a specific industry or geographic region, but most provide significant latitude to target selection sponsors. Historically, most SPACs sought out companies with positive EBITDA. But several recent high-profile deals featured pre-revenue companies with alluring investment concepts.

- SPACs relatively low-risk structure — combining the ability to recoup the initial investment at their discretion with the opportunity to participate in the upside of a privately negotiated deal — is attractive to many investors. IPO investors receive a "unit" that includes one stock share and either a whole or fractional warrant to purchase additional shares. In the past, this structure enabled trading strategies that incentivized aggressive hedge funds to extract further compensation in exchange for backing proposed acquisitions.

- PIPEs, or private investments in public equity, have become a more common feature in closing SPAC acquisitions, either to replenish cash lost to trust redemptions or to increase the overall transaction size to meet the target company's growth objectives. Participation in PIPEs by high profile institutions may signal that "smart money" is backing the company in size. On the other hand, if PIPE investors receive preferential deal terms, this can further complicate the capital structure post-closing.

All of these participants in the SPAC structure may have conflicting incentives, so aligning the incentives to create a successful new public entity requires a thoughtful selection and negotiation process.

Learn More About MBP SPAC Audit Specialists

Growth of SPACs

The origins of the SPAC date back to the "blank check" stocks of the 1980s, which were typically penny stocks traded on the OTC markets and had relatively few investor protections. This market virtually disappeared when the SEC disciplined the most active brokerage firm behind these offerings and implemented Rule 419 to eliminate prior abuses. The modern SPAC was born in 1993 when Early Bird Capital completed a blank check IPO, which technically avoided the “penny stock” rules with offering sizes over $5 million and units priced at over $4 per share, but that incorporated investor protections enshrined in Rule 419.

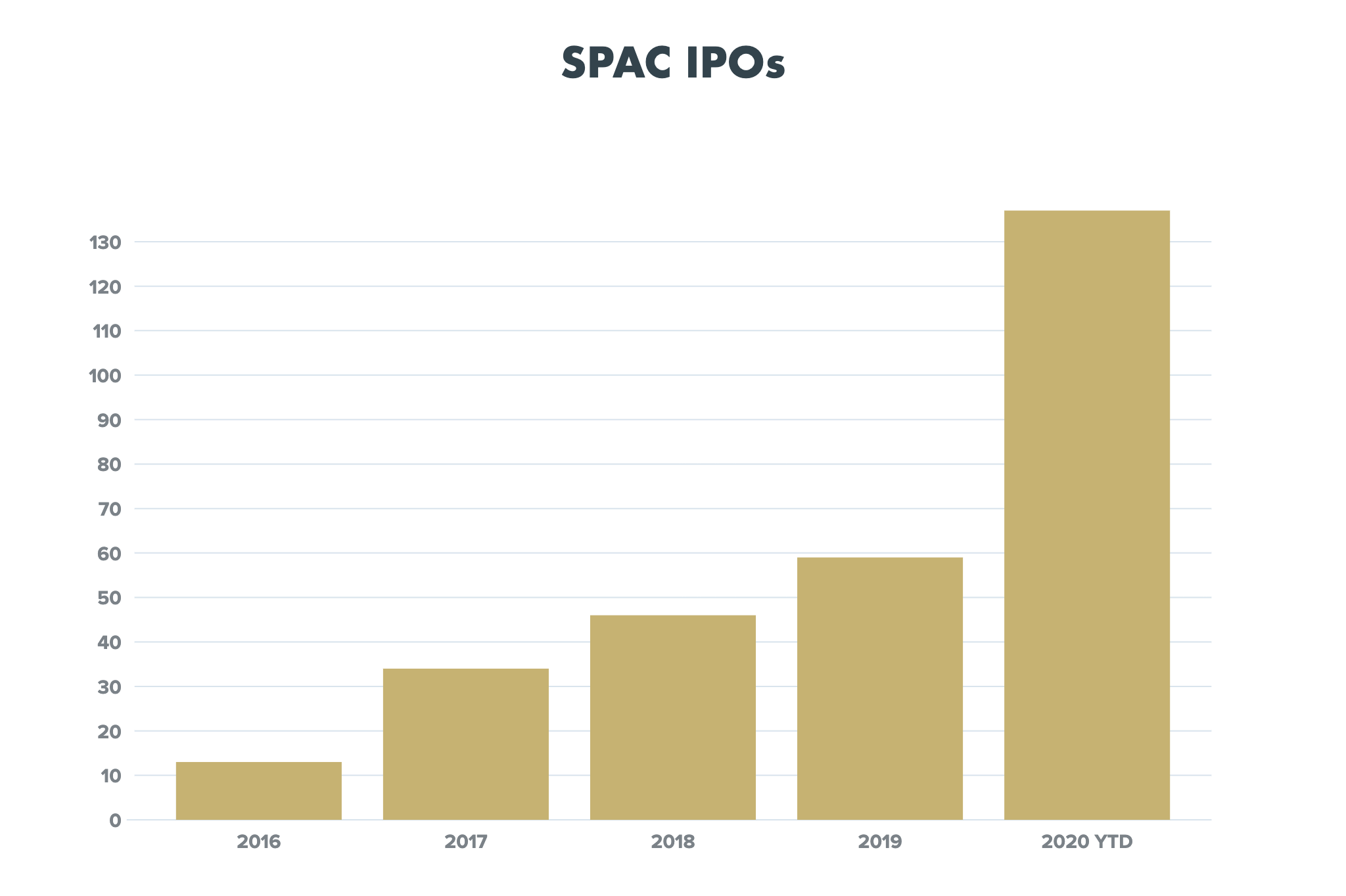

While the popularity of SPACs ebbed and flowed, the number and size of SPAC offerings have continuously risen since 2016, before exploding in 2020. (See chart below.) As of the end of September of 2020, SPACs have accounted for 45% of new issues and 44% of total capital raised by U.S. IPOs. SPAC sponsors now include a range of highly prominent names, including hedge fund manager Bill Ackman of Perishing Square and venture capitalist Peter Thiel, baseball savant Billy Beane of “Moneyball,” and former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

As SPACs have proliferated and ballooned in size, the competition for acquisition targets has grown more heated. SPAC sponsors may be more flexible in key deal terms, especially as the clock approaches midnight, and they face the prospect of their coach and liverymen reverting to pumpkins and mice.

Key Considerations for Management

SPACs potentially offer several advantages over either private equity or late-stage venture investment or a traditional IPO. However, they have several unique features that management needs to be aware of when evaluating a potential deal.

- Speed to Market – A SPAC potentially provides an accelerated path to going public, with deals able to close in two to three months, versus a typical six- to nine-month IPO process. But meeting this timetable requires a company to have two or three years of audited financials and produce extensive disclosures. Speed to market is particularly important in periods of market turbulence when the IPO "window" can close before the SEC review process is complete.

- Negotiated Valuation – When merging with a SPAC, the target company can hammer out the initial valuation directly with the SPAC sponsors instead of relying on the last-minute pricing discussions between underwriters and large institutions in an IPO. Additionally, the target company is permitted to share financial projections as part of the filings with the SEC, so that pricing may better reflect anticipated future performance. Some have argued that SPACs can provide companies with a lower cost of capital by avoiding the “IPO discount” applied to entice buyers to new listings. [i] However, as a closing condition, the SPAC investors must believe that the post-merger company's shares will be materially more valuable than the cash in trust. If the valuation is stretched too far, redemptions will cripple the deal.

- Public Market Expertise – As SPACs have attracted more high-profile sponsors, these advocates' endorsement and capital markets expertise may provide significant added value to the newly public company. In some instances, some SPAC sponsors may play an ongoing role in management or join the board post-closing. [ii] Successful hedge-fund or venture-capital investors may have a megaphone to amplify the promise of the investment story. Their knowledge of disclosure and governance expectations can help management teams from emerging markets, which may be less familiar with U.S. requirements.

Some of the risks associated with SPACs include:

- Dilution – Because of the typical 20% founders’ shares awarded to SPAC sponsors, all other shareholders will experience immediate dilution once the business combination closes.[iii] In comparing the cost of capital to other funding sources, management must analyze investor warrants' future impact, sponsor warrants, and any private placement to derive the fully diluted implications of the combination on their valuation.

- Reputational Risk – While the profile of SPACs in 2020 is quite different from what it was decades ago, the returns for SPACs that have closed business combinations have historically far worse than traditional IPOs. Some investors may assume that SPAC targets have been poorly vetted or were unable to muster support from investment banks for an offering. Management should do everything possible to have flawless financial reporting and internal controls to overcome this presumption.

- Investor Rejection – The most significant risk associated with the SPAC vehicle is that the company will invest the time and money required to produce audited financials and required disclosure documents only for the deal to fail. Failure can occur because a sufficient number of shares voted against the transaction. Or even if a merger is approved, cash redemptions may exceed the minimum required by the company. While the number of SPAC liquidations has been low in recent years, a down-trending market could cause more deals to fail.

Negotiating the SPAC Deal

An enticing aspect of SPACs for private companies seeking capital is that "Everything is negotiable," to quote Bill Gurley. While the SPAC IPO prospectus determines much of the structure, there are several essential deal terms on which the private company's management should focus. Some companies will even organize a competitive “SPAC-off” to meet with multiple SPACs that fit their industry profile and capital needs. The closer that SPACs get to forced liquidation, the more flexible their sponsors are likely to be.

Some of the key deal terms include:

- Founders’ Shares – Desirable companies may be able to negotiate that a portion of these shares is allocated to the private company to reduce dilution. Or if the SPAC sponsors plan to be long-term partners, they may agree to escrow their shares until the share price hits certain thresholds. Founders’ shares should also be canceled, and the escrowed portion of the underwriters’ fees should be reduced pro-rata with IPO redemptions to balance the anticipated proceeds with negotiated dilution.

- Minimum Cash & Shareholders – One great advantage that SPACs offer is that they have already raised sizable capital. However, the operating company needs to understand that trust funds are not truly committed capital, as investors can redeem their shares at closing for cash. Based on its growth strategy and the investments required to meet investors' financial objectives, the target must set a minimum threshold for the deal to be viable. In some cases, the SPAC sponsor or another investor may enter into a "forward purchase arrangement" to invest in a specified size required to meet the minimum cash closing condition. Equally important is that the company retain a sufficient number of round lot shareholders to meet the requirements for continued listing on the stock market where the IPO took place since otherwise, it would face the threat of delisting.

- Closing Expenses – While the SPAC has already incurred legal and accounting expenses with its IPO, these are typically de minimis. By contrast, closing the deal will require a full PCAOB-compliant audit and extensive disclosures, including a proxy statement, potentially a Form S-4 registration statement, and a “super 8-K” that contains all the information contained in a Form 10 registration statement. The SPAC and target company must agree who will bear the responsibility and expense of generating all of these elements. If the SPAC fails to close, the target company typically has no recourse to the IPO proceeds held by the SPAC trust, so all expenses are "at risk."

- Governance – In some instances, the SPAC sponsors or associated PIPE investors may insist on a certain number of board seats to influence the newly public company's decisions post-closing. For a target company with limited expertise with public markets, these board members may add significant value through their strategic advice. But it is essential to make sure that the board and its committees' composition complies with the independence rules of the exchange where it will be trading. The board should also establish clear rules for handling conflicts of interest that may emerge where the SPAC sponsors have strong financial incentives.

These are a few of the more critical deal terms to be negotiated. The target company's management will still want to retain legal counsel with deep experience with the fast-evolving SPAC market. SPAC founders are generally highly sophisticated financial experts and have no obligation to educate the target about what they can or should be requesting.

Getting to Close

Once the essential deal terms have been negotiated, there will be an intensive push to close the SPAC business combination in a highly compressed timeframe. At this point, the SPAC sponsors and target management work as partners to achieve two key objectives:

- Complete all the required disclosures to close the deal before the clock runs out.

- Convince existing shareholders to vote in favor of the transaction and retain ownership in the newly public company while attracting enough investors sufficient to bid the share price above liquidation value.

In general, if the SPAC share price trades materially higher than the per-share value of the cash held in trust, this is a signal that the transaction is likely to be approved, and most investors will retain their ownership. Suppose the share price trades at or below liquidation value. In that case, this signals that investors have significant doubt if the business combination will create value for shareholders, and the deal may fail. Management of the target company needs to join the SPAC founders in meetings and phone calls with sizable holders to educate them about its strategy and prospects.

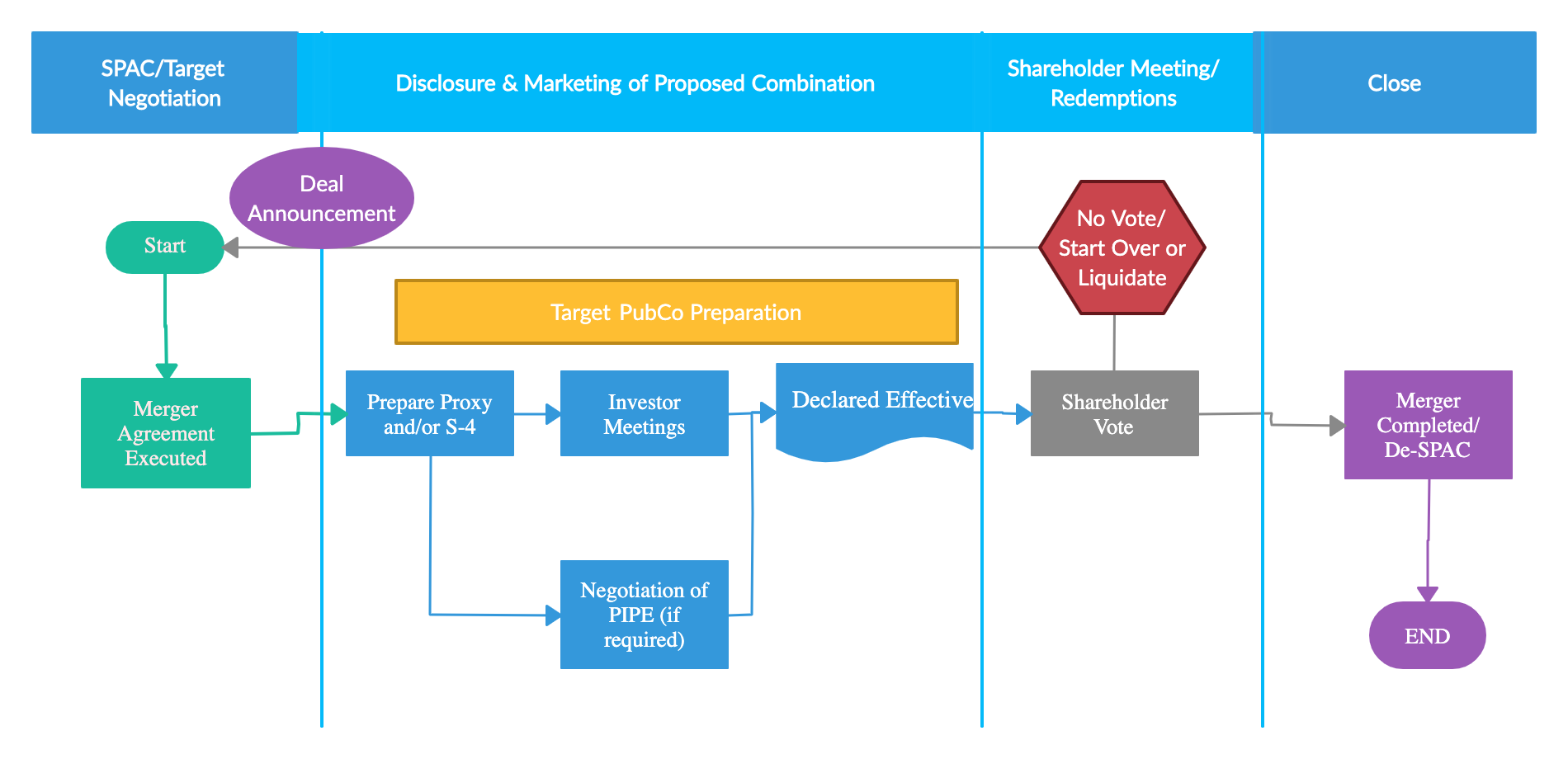

The diagram below lays out a typical process to go from deal announcement to closing.

During a compressed timeline of 2-6 months, management of the target company must produce extensive financial and operational information required for the Proxy Statement or combined S-4 registration statement, including:

- Audited financials for two years and up to three years compliant with GAAP and SEC rules and compliant with PCAOB audit standards.

- Interim financial statements.

- Pro forma financial information presenting the effects of the business combination.

- Extensive MD&A discussion of operating trends and risk factors.

- Potentially financial forecasts that provided the basis for business valuation.

Working with the professionals and SPAC sponsors, management must be prepared to respond in a timely fashion to all SEC comments and information requests. At the same time, management will be conducting what is essentially a second IPO roadshow to generate enthusiasm for the deal and tally the votes.

Preparing to Be Public

Assuming that the deal closes, the target will become a public company, usually with new names and trading tickers for both the common shares and warrants. A "super 8-K" must be filed with the SEC within four days of closing, and from that point forward, management is responsible for remaining current with all reporting obligations, including the 10-K annual report, 10-Q quarterly reports, and 8-K interim reports.

To ensure that this transition occurs smoothly, the company should develop a comprehensive public company strategy that includes:

- Financial Reporting – The company’s finance team must be well versed in SEC and US GAAP reporting and be capable of timely monthly and quarterly close schedules and working efficiently with independent public company accountants.

- Internal Controls – The company will likely need to strengthen its internal controls over financial reporting and create robust systems that can be tested by auditors and communicated to the board's audit committee.

- Budgeting and Forecasting – Given the importance that shareholders place on meeting financial expectations, the company must develop mature forecasting capabilities based on reasonable assumptions.

- Tax Planning – The target company should carefully evaluate all the tax implications and how the business combination is structured. In some cases, an umbrella partnership C-corporation (or Up-C structure) can provide preferential tax treatment for the pre-IPO investors in the SPAC merger. They enter into a tax receivable agreement to avoid double-taxation.

- Investor Relations – The new public company will have a whole new constituency who will require significant time from senior management: its shareholders. Often, companies that go public via a SPAC have far more limited analyst coverage and a more concentrated shareholder base than a traditional IPO. A comprehensive investor relations strategy is essential to develop liquidity and visibility for the stock.

Summary

The explosion of the SPAC market in 2020 will create a unique window for private companies to enjoy an accelerated path to raise capital and achieve public status over the next 24 months. While the SPAC structure complexities should lead management to approach these deals with their eyes wide-open, the opportunity to secure favorable deal terms is undeniable. Alignment of interests will be critical to crafting terms that benefit target companies, the SPAC sponsors, and public market investors alike.

Marcum BP SPAC Practice

Marcum LLP has consistently been ranked as one of the top auditors for SPAC IPOs in the world, taking the #1 spot in 2019. Marcum has represented issuers, worked with underwriters and targets of special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), and has wide-ranging experience in initial public offerings and subsequent business combinations entered into by such companies.

Marcum Bernstein & Pinchuk (Marcum BP) is highly experienced in providing independent audits and advisory services to both SPAC IPOs from Asia and operating companies based in Asia preparing for a business combination with a SPAC. We are registered with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and have significant experience coordinating with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and major U.S. stock markets including NASDAQ and the New York Stock Exchange.

[i] See Bill Gurley’s blog “Going Public Circa 2020; Door#3: The SPAC,” where he states: “SPACs have a much lower cost of capital versus a standard IPO.”

[ii] See Reid Hoffman “Reinventing the SPAC,” where he claims that the SPAC that he founded with Mark Pincus provides “venture capital at scale” and that the sponsors will serve as “a major financial investor with patient capital who will partner with the CEO for the long term (i.e., the next ten years) to take the necessary risks to reinvent the business and capitalize on opportunities for innovation and growth.

[iii] Pershing Square Capital’s recent record, $4 billion SPAC, Pershing Square Tontine, is the first SPAC to eliminate the 20% founders' shares, and Bill Ackman has been critical of this standard feature, saying: "I thought it was egregious. It is one reason the track record of SPACs is often poor."